How I fell for Mumble the owl

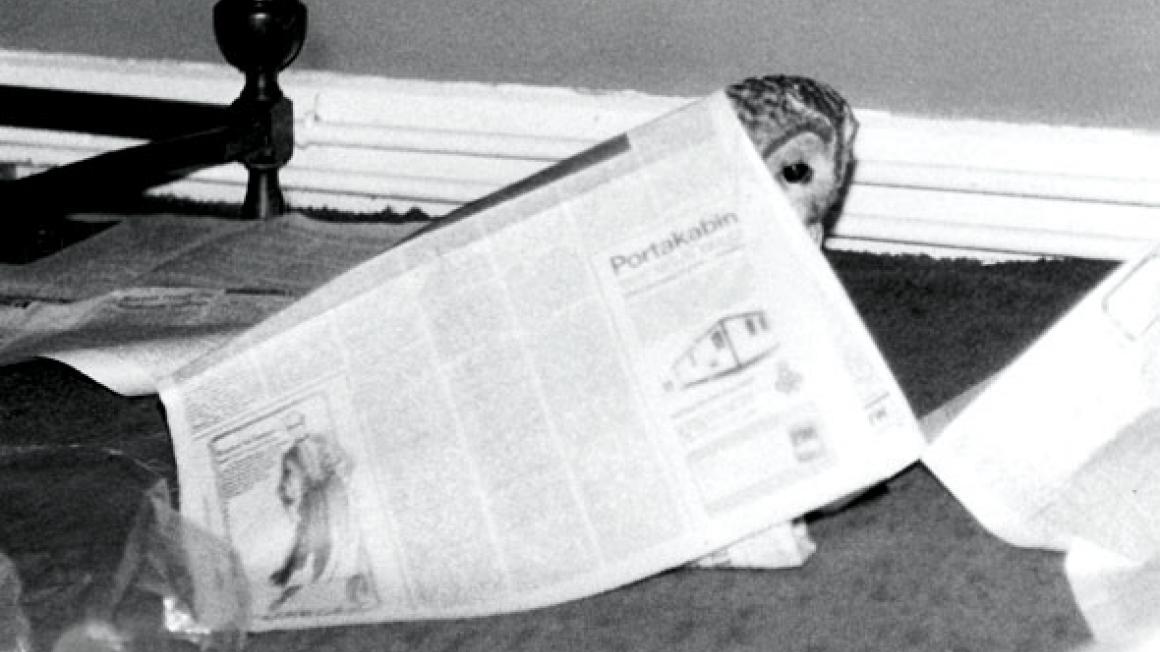

This problem was one of the unavoidable consequences of sharing a flat with Mumble. Others were the need to spread newspapers and plastic sheets everywhere (you can’t house-train a bird); nurse friends’ injured scalps during Mumble’s adolescence, when she rapidly turned from an animated cuddly toy into a strictly one-man and highly territorial virago; and having to explain to a new girlfriend who went looking for icecubes why the freezer was full of dead, day-old chicks.

I owed my unusual flatmate to an impulse I had discovered in myself while visiting my brother Dick, one of whose hobbies was falconry. The idea of training a falcon in a south London high-rise flat was obviously ridiculous, but tawny owls have a reputation for making happy pets, so in spring 1978 I ordered an egg from a licensed breeder.

I could never have squared it with my conscience to capture a wild bird and cage it; Mumble was hand-reared from the egg, and in all the years I lived with her she was never tethered. (I must stress that all wild hunting birds, their eggs and hatchlings, are strictly protected by law. If you come across an owlet in the woods you should never ‘rescue’ it unless it is obviously injured and in danger – nine times out of 10 it’s just exploring.)

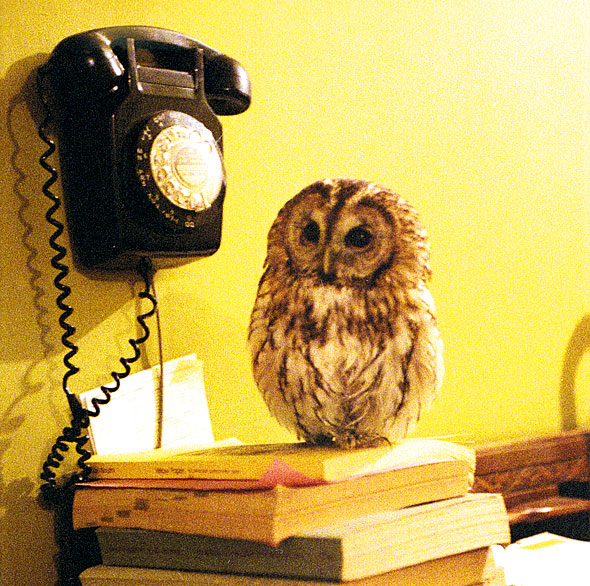

With Martin

With MartinThe day came when I walked into Dick’s farmhouse kitchen to see a small, plump creature dressed head-to- foot in grey fluff sitting calmly on a chairback. She blinked her huge black eyes at me, said ‘Kweep!’ very softly, and jumped up on to my shoulder. My heart turned over, and I was her slave for the next 15 years.

Watching her learning to fly and groom herself was endlessly fascinating and amusing, though not without some expense. It took her months to master neat landings; at first she simply flew full-tilt at her selected target, and I had to replace several knockedover table lamps. She also loved ripping up anything rippable (including my shoelaces), and destroying house plants. Her main perch was the top of the open living-room door, but she also spent hours on end sunning herself on a Roman bust that I kept on a pedestal beside the biggest window. (Owls like sunshine – they only hide among the leaves in daytime so that they can sleep without danger of interruption. In the wardrobe-size cage that I built on my balcony, Mumble would often sunbathe on the floor, lying flat on her front with out-spread wings and her slitty-eyed face turned upwards.)

I would also often hear her splashing about in her water dish. One evening she jumped into the deep kitchen washing-up bowl, and soaked herself so thoroughly that I hardly recognised the alarming tangle of spiky black feathers that came stomping into the living room, muttering crossly to herself. I lifted her on to a shelf close to an overhead light, where she spent hours drying off in the warmth until she could fly again. From the first, I was surprised to discover that my hand-reared tawny had a capacity for companionship that went well beyond her interest in my providing supper. As lazy as a wellfed cat, she would often sit and doze on my shoulder with one taloned foot tucked up ‘into her pocket’. Many times she would demand my touch, climbing on to my lap or my desk and craning her face up to be nuzzled, making crooning noises and nibbling at my beard. She particularly loved being nuzzled among the short, thick feathers between her eyes, and after these ‘necking sessions’ she would remain sitting fluffed up in a sort of afterglow of pleasure. I found these demands for mutual preening delightful (she smelt delicious – warm, clean, and sort of biscuity.)

After we moved down to Sussex in 1981, I built her an aviary with country views, so we didn’t see so much of each other every day. It was sometimes hard to figure out what persona she had cast me in on any particular occasion. Wild tawnies mate for life and share a hunting territory, although they live separately for part of the year. Both in the flat and in the aviary, she chased away hopeful suitors with every sign of territorial fury.

In the autumn and winter in Sussex she was indifferent to me, though always civil, but during the moulting months from May to September, her mood changed completely. As clingy as a sickly child, she would constantly seek my company and touch, perhaps for reassurance while she felt in poor condition. Then again, on one occasion she flew to my shoulder with a disgusting beakful of half-eaten chick, and tried repeatedly to feed me with it – when I declined, she tried to stuff it into my ear.

Mumble lived for 15 years, and could have lived for at least another 10, had an intruder not broken into her aviary one night. This must have driven her into a frenzy of rage; I found her lying spread-winged in a clump of daffodils, the victim of a heart attack in mid flight. All these years later she still sometimes appears in my dreams; and whenever she does, she brings a surge of grateful fondness into my mind.

Martin Windrow’s book, The Owl Who Liked Sitting On Caesar, is published by Bantam Press, £12.99.