THE LADY & THE FIRST WORLD WAR

The first mention of the war appeared in the 6 August 1914 issue, two days after Britain joined the conflict and declared war on the German Empire. And the sentiment was stark: ‘At the moment of writing every thing – social life, holidays, home politics – is overshadowed by terrible war clouds.’

But it also ridiculed the commonly held idea that ‘War is not a woman’s business’. With Britain’s ladies facing the prospect of rising food costs and the agony of ‘seeing loved sons and husbands and brothers go off on their dangerous duties’, the editorial maintained that this dismissive attitude ‘will be seen to be a very hollow and false figure of speech’.

The theme was continued the following week in the 13 August issue, which celebrated the extraordinary courage of Britain’s women: ‘The summons that calls out our fighting men on both sea and land to be ready to face the foe, and sustain, now as ever, the honour of their country, scarcely less tests the courage of those who have to stay at home and endure the sickening suspense that attends each interval that lies between the arrival of news from the seat of war.

‘This passive form of courage is largely shared by women, most especially those who have dear relatives or friends at the front.’

WOMEN TO THE FORE

The magazine also anticipated that all would suffer, both at home and abroad, and that charity would play a key role in the nation’s survival. ‘The poor are certain to become poorer still, and so have to bear the heaviest burdens of the hard times in store, even for the rich,’ a 13th August editorial read. ‘Self-denial, needful for one’s self, may enable us also to help others…’ Certainly women would have to play a central part in alleviating this suffering. ‘The fact that one cannot bear arms does not excuse anyone from helping their country’s cause by fighting such foes as misery, pain, and poverty, the dire followers of all battles, whether lost or won,’ the article continued.

Indeed, The Lady made clear how eager the nation’s women were to do their bit – bemoaning the fact that many were frustrated that they couldn’t play an even greater role.

In his excellent, bestselling book about the opening months of the Great War, Catastrophe, eminent historian Max Hastings makes numerous references to The Lady. In one editorial quoted by him, this frustration is particularly evident. ‘Soon all the committees will be formed, the needlework in hand… the chosen nurses in their places – every woman in the land doing all that is possible for her to do in the way of special work… Yet in spite of everything there will still be in all our hearts a sensation of yearning to do more.’ Nevertheless, many did everything they could.

A month or so after the start of the war, for example, The Lady reported how the Duchess of Devonshire, Lady Lansdowne, Lady Pembroke, Lady Castlereagh and Lady Kerry, ‘advocated the wearing of a white badge on the arm as a sign of grief for the brave dead who fall on the field of honour’.

Meanwhile, in The Lady 13 August 1914 issue, it was revealed that Lady Dudley organised a voluntary field service hospital, while the Duke of Sutherland had offered up his grand coastal castle, Dunrobin, for the treatment of the wounded. The King and Queen (George V and Mary of Teck) were also out and about during this period of ‘great national stress’.

‘During a week crowded with epoch- making events, the issue of which may change the face of the world,’ The Lady reported, ‘[they] have born their parts nobly and calmly.’

In fact, this magazine portrayed the Royal family as paragons of the great British stiff upper lip.

‘Their splendid attitude can only serve as a stimulus and example to all their subjects,’ said the editorial.

As Hastings points out in his book, The Lady also sought to help its readers deal with a new set of problems. Within months of the outbreak of war, food was certainly becoming scarce. But how to economise? The Lady certainly advised always keeping pudding, which bolsters morale and ‘is especially looked forward to by the younger members of the family’.

The magazine even featured a Daily Difficulty column, dealing with such issues as how women returning to Britain from elsewhere in the Empire should fi nd their feet.

As Hastings reveals, The Lady advised that ‘newcomers from abroad should post notice of their arrival in a reputable newspaper’; while another edition urges housewives to deal with the stress of war by planting unused plots with turnips, carrots and onions.

Some of the editorials appear rather pompous today. In one, The Lady bemoaned how London’s high-society restaurants were suffering because of an absence of staff . Many of the French, after all, had returned home to fight, the Germans had been recalled or dismissed, and only the Swiss and Italians were left ‘to wait upon the visitors’. It also noted, however, how quickly the capital adapted to the new way of life war brought with it. ‘The stores and provisions dealers report a decline of “panicky” buying, and the great city seems very much as usual,’ the magazine reported on 20 August 1914.

Attitudes to profligacy had changed, though, and some members of the upper classes, it seems, weren’t that happy about it. The same edition noted, ‘In not a club nor a restaurant can people indulge in costly luxuries without the disapproving frowns of those near to them. There is such a sober and responsible spirit that fopperies and ostentations have almost disappeared from the streets.’

The magazine’s editorials add colour to many aspects of the war, off ering a very British perspective of the other belligerents, too.

Take the magazine’s view of Russia, for example, a nation whose high life, in the words of Hastings, ‘exercised a fascination for Western Europeans’.

The Russian Empire, ruled by Tsar Nicholas II and fighting on Britain’s side, was described by The Lady thus: ‘This vast country, with its great cities and arid steppes and extremes of riches and poverty, captures the imagination… and English people, generally speaking, are liked and welcomed by Russians.’

The Lady also waxed lyrical about Russian society’s attitude to educating children. ‘One learns that the girls of the richer classes are brought up very carefully. They are kept under strict control in the nursery and the schoolroom, live a simple, healthy life, are well taught several languages… with the result that they are welleducated, interesting, graceful, and have a pleasing, reposeful manner.’

PEACOCK KAISER

The Lady, in the editorial of a September 1914 issue, also painted a portrait of Germany’s peacock Kaiser – and the gargantuan task faced by those whose job it was to care for his innumerable uniforms.

‘Though he has abandoned the uniforms of the British Admiral and Field Marshall, the Kaiser has enough left to satisfy all reasonable desire for change of costume,’ the report in The Lady revealed, acidly. ‘In all, his uniforms are said to total some 3,000, and he employs a head valet with a dozen underlings to take care of them.

‘Each of these men is an expert on military uniform, for it is no light task to remember the accessories in the way of swords, epaulets, sashes and so forth.’ The juxtaposition between images of ordinary soldiers fi ghting in the boggy trenches and this snapshot of the Kaiser’s vast military closet is striking indeed.

But it was Belgium that received most praise in the early stages of the conflict. ‘Little Belgium, smallest and most sorely pressed of the nations engaged, off ers of them all the most splendid example of indomitable courage,’ The Lady wrote.

As Hastings highlights, the full, vivid horrors of the battlefield itself are often overlooked, an oversight that suggests some echelons of society were rather too keen to bury their heads in the sand.

In one rare insight into life on the frontline, the magazine compared the British war machine to good, old-fashioned housekeeping.

‘The task of feeding an army of hard-worked men on a modern battlefield is a truly wonderful achievement – “housekeeping” you may term it, upon a colossal scale. Because we have command of the sea, however, provisioning our Expeditionary Force becomes a fairly easy matter.’

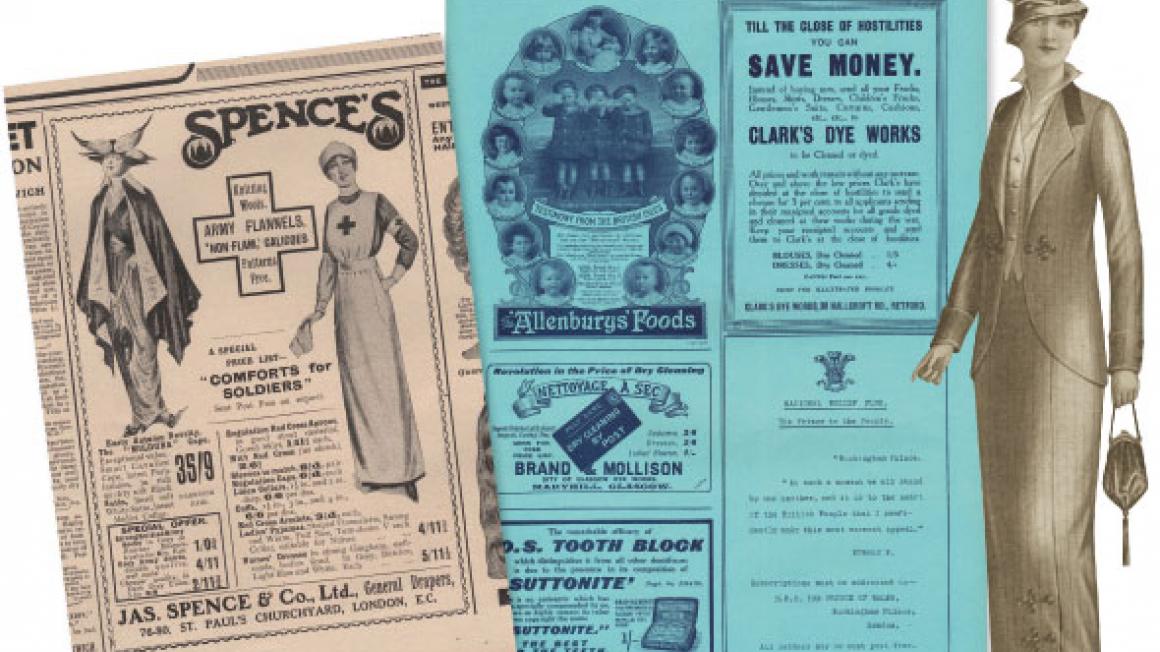

But it isn’t only the editorial that draws back the curtain on 1914 British society; the advertisements can be just as enlightening.

In the 10 September 1914 issue of The Lady, for example, an advertisement for Clark’s Dye Works of Retford (on the opening pages) highlighted how families across the country were feeling the pinch – just six weeks after the start of war. ‘Till the close of hostilities, you can SAVE MONEY,’ it promised. ‘Instead of buying new, send all your Frocks, Blouses, Skirts, Curtains, Cushions etc. to Clark’s Dye Works to be cleaned or dyed.’

In the same issue, there was also a message from HRH The Prince of Wales, in support of the National Relief Fund. ‘At such a moment we all stand by one another,’ it read. ‘And it is to the heart of the British people that I confi dently make this most earnest appeal.’

Perhaps most poignant of all, however, is an advertisement for dressmaker WM Barker on page 3 of the 20 August 1914 edition:

‘MOURNING’ the main line read, promising beneath, ‘Urgent mourning orders dealt with at once. Assistants sent to all parts.’

After a carefree summer, this one simple advertisement reminds us that already this was a nation dealing with the daily threat of death and loss, something we should never forget, even 100 years on.

Catastrophe: Europe Goes To War 1914, by Max Hastings, is published by William Collins, priced £30.

BREAKING NEWS

Copies of The Lady from 1914 are full of fascinating details about First World War Britain, including…On 21 August 1914 there was a total solar eclipse. The phenomenon was visible from northern Europe.

In 1914, the London County Council provided elementary schools with dolls, model houses and nurseries to ensure that young girls would grow into effective housekeepers.

Mons, the site of the first engagement between British and German troops, was also believed to be the place of origin of ‘Mons Meg’, Edinburgh Castle’s huge six-ton cannon.

Theatre became more accessible in 1914. Many London theatres reduced ticket prices and removed their ban on ‘street clothes’ in the stalls.

In autumn/winter 1914, the Great War influenced fashion – the trend was for military styling and black ladies’ dresses and coats.