How to keep your husband out of the pub...and other tips from a forgotten heroine

As with Mrs Beeton, Woolley’s books – her first was The Ladies Directory in 1661 – not only include recipes, but also advice on marketing, menus and how to behave. Unlike Mrs Beeton’s, Woolley’s books address cooks and kitchen maids as much as the ladies of the house.

There are conflicting theories about Hannah Woolley’s life, but she was orphaned at 14. Unlike most penniless girls at the time, however, she worked as a teacher and ‘began to consider how I might improve my time to the best advantage’.

At 17 she was taken up by a noble lady who recognised a ‘perfect treasure’ and encouraged her education, and in 1647, married Benjamin Woolley, Master of an Essex Grammar School. The marriage was happy and they had at least four sons.

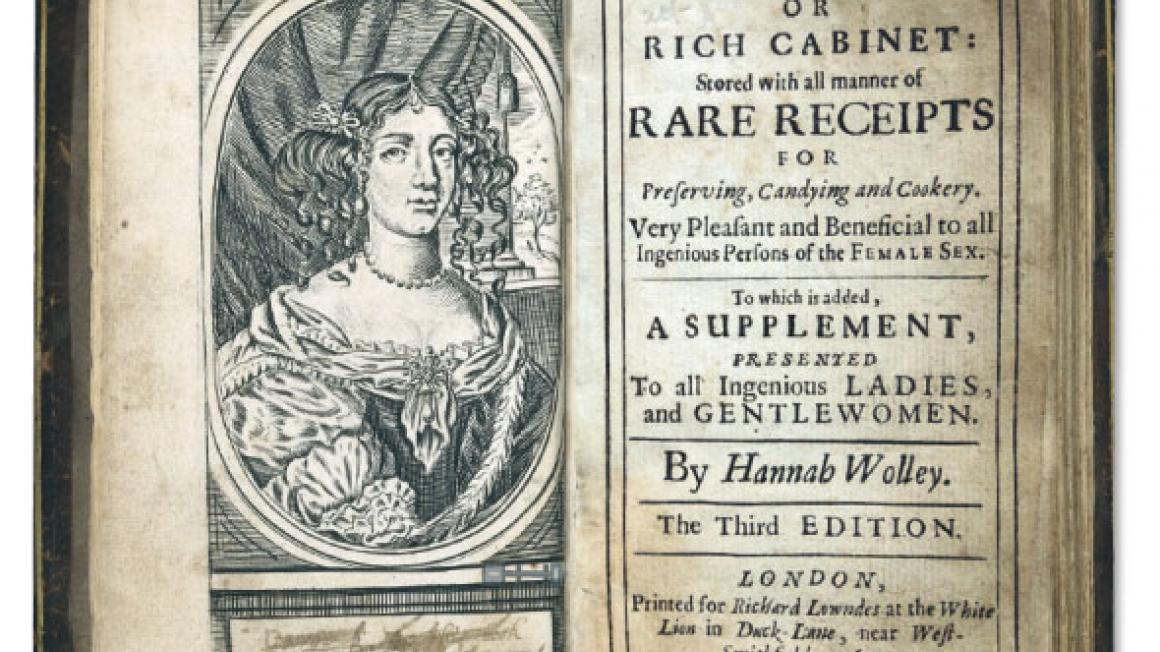

In 1661, however, Woolley was widowed. It is thought that at this time she worked for a Lady (Anne) Wroth. More signifi cantly, it was during her fi rst widowhood she decided to selfpublish, becoming the fi rst woman in England to put her name to a book, and to make a living from doing so.

The Ladies Directory was not cheap at six shillings. Still, within a few years she had to reprint it, and her next, The Cooks Guide (1664), which featured more recipes, was paid for by a publisher.

Woolley married again in 1666 to a widower, Francis Challinor, and in 1670 she published The Queen-Like Closet. She promised the reader that ‘it is worthy of the title it bears, for the very precious things you will fi nd in it.’ It ran to fi ve editions.

Her next book, The Accomplish’d Lady’s Delight (1672), was a cunning revision of the fi rst two in one volume. In the preface she continues in her work of self-promotion. She tells the reader that the book ‘containeth more than all the Books that ever I saw Printed in this Nature, they being rather Confounders, than Instructors’. She also set forth her stall for being remembered, writing ‘I would not willingly… be forgotten when I am dead.’

After her second widowhood, Woolley lived in London with her son Richard. She continued to work, making a living selling medicines, and she also ran what might have been the fi rst domestic employment agency, training up servants as well as fi nding them jobs.

Hannah Woolley is no longer a household name, but she was a great food writer – and an impressive early feminist, too.

HER BOOKS

The Ladies Directory was mostly about medicine, confectionary and preserving fruit and vegetables (an important skill in a pre-fridge world); The Cooks Guide written to complement it, was more recipe based. Although aimed at employees, there was also the awareness that, as many servants still could not read, the employers might themselves need a bit of a hand.Woolley’s works reveal a great deal about the accomplishments it was thought a 17th-century woman, or at any rate ‘lady’, needed. As well as the presumably ladylike arts of preserving fl owers and fruit, she was expected to make jams and pickles. She should also have some knowledge of basic medicine.

Her cure for breast cancer (‘Take the Dung of a Goose, and the Juice of Celandine, and bray them well in a mortar together, and lay it to the Sore, and this will stay the Cancer, and heal it’) might explain why scientists are still working on this problem. But her grasp of wrinkle cures and cosmetics ‘some Rare Beautifying Waters, Oyls, Oyntments, and Powders, for Adornment of the Face and Body, and to cleanse it from all Deformities that may render Persons Unlovely’ was probably more efficacious.

She also wrote with passion about the right of girls to be educated: ‘I… must condemn the great negligence of Parents, in letting the fertile ground of their Daughters lie fallow, yet send the barren Noddles of their sons to the University, where they stay for no other purpose than to fil their empty Sconces with idle notions,’ pointing out that ‘had we the same Literature, he [man] would find our brains as fruitful as our bodies.’

She also wrote wryly of fashion, suggesting that the ‘Farthingals of old, were politickly invented to hide the shame of great Bellies unlawfully puft up.’

Her rules for table manners would apply as well today: ‘Fill not your mouth so full, that your cheeks shall swell like a pair of Scotch bag-pipes… Gnaw no bones with your Teeth, nor suck them to come at the marrow.’

She even advises on how to keep a husband from the pub: ‘Let whatever you provide be so neatly and cleanly drest that his fare, though ordinary, may engage his appetite, and disingage his fancy from taverns, which many are compell’d to make use of by reason of the continual and daily dissatisfaction they find at home.’

For a woman writing in the 17th century, a lot of what she says is refreshing and modern. Perhaps her only rule with which one would entirely disagree today is her opening advice on marriage: ‘There are these two Essentials in Marriage, Superiority and Inferiority. Undoubtedly the Husband hath power over the Wife, and the Wife ought to be subject to her Husband in all things.’

But what of her recipes? Woolley certainly cared about practicality and economy. She included recipes using up leftovers, but because she knew that the food you cook announces your social status, she also included more ‘modern’ flavours such as anchovies, wine and cream.

To today’s reader, Woolley’s recipes are confusing and she rarely gives cooking times. (Remember, though, that with most of the cooking done on an open fire, cooking times were bound to be more varied.)

Her quantities are also vague; in one recipe she says to cut bread in slices ‘about the bigness of a groat, and as thin as Wafers’. Elsewhere we are told to cut meat the size of a pullet’s egg. One much-used ingredient in Woolley’s kitchen is butter. Her recipe for scrambled eggs involves more than a pound of it. But there are rather stranger ingredients, too: a cod’s head, and minced chicken’s brain for adding to a fricassee.

There are certainly recipes of great historical interest. Who can forget the furmity laced with rum that caused Michael Henchard to sell his wife before he became Mayor of Casterbridge? Thomas Hardy calls this drink ‘antiquated slop’, but looking at the recipe (without the rum) you can see it is a wholesome and cheap combination of a soup and a drink for the poor: barley, cream, ginger, mace and nutmeg for taste, eggs to thicken and (of course) sugar.

In The Gentlewomans Companion, she includes a list of points by which a housewife should live; and in these often cash-strapped times, they are as apposite now as they were in 1675: ‘First to buy and sell all things at the best times and seasons. Secondly, to take an especial care that the goods in the house be not spoiled by negligence… Let me counsel you not only to avoid unnecessary or immoderate charges… but above all suffer not your expence to exceed the receipt of your Husbands income.’

Hannah Woolley, it seems, still has much to teach us.

Cooking People: The Writers Who Taught The English How To Eat, by Sophia Waugh, is published by Quartet Books, priced £20.