LIBERTY & FREEDOM

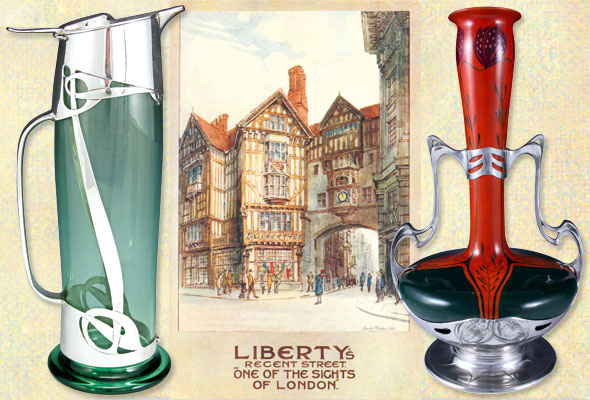

From left: A claret jug from 1902, designed by Archibald Knox. A postcard showing Liberty’s new faux Tudor building circa 1930. A ‘Zsolnay’ ceramic vase with ‘Osiris’ pewter mounts made in Germany circa 1905

From left: A claret jug from 1902, designed by Archibald Knox. A postcard showing Liberty’s new faux Tudor building circa 1930. A ‘Zsolnay’ ceramic vase with ‘Osiris’ pewter mounts made in Germany circa 1905Yet despite his dandyish penchant for wearing velvet jackets with informal neckties and a nice line in chic friends, his background was far from that of a bohemian trailblazer. Arthur Lasenby Liberty was born on 13 August 1843 above his father’s draper’s shop on Chesham High Street, and he grew up watching his father ply his skilful trade. It was here that he developed the feel for fabrics and upholstery that would later help him establish his world-respected brand.

Although the family was comfortable, money was scarce, so at 18 he went to work for Farmer and Rogers, a shawl and cloak retailer with royal patronage. Over the next 10 years he honed his skills in their basement, inventing a separate home wares and fashion department, before branching out on his own with a £2,000 loan from his future father-in-law.

Liberty & Co was born in a shortlease premises directly opposite his former employers on upmarket Regent Street. His gamble paid off , the new business prospered and over the following decades he gradually bought up neighbouring properties until he owned an entire ‘island’. The faux Tudor building that stands on Great Marlborough Street today, with its gilded weathervane and the coats of arms of Henry VIII’s six wives on the main doors, was a deliberately constructed conceit built after his death but very much in keeping with his principles. A series of small, intimate, interconnected rooms centred around three impressive atriums gave the store’s clientele a taste of rambling through a private, elegant stately home, with all the pieces fitting into a setting of your imagining. For Liberty, it was never just a shop; it was a lifestyle.

Liberty’s ‘Lotus’ collection, photographed in the Royal Opera House circa 1960

Liberty’s ‘Lotus’ collection, photographed in the Royal Opera House circa 1960From the very beginning, Liberty was aware he was on the crest of a social revolution. Architects he knew and admired, such as Lutyens and Voysey, were building houses for the successful middle classes who also formed the bedrock of his customers.

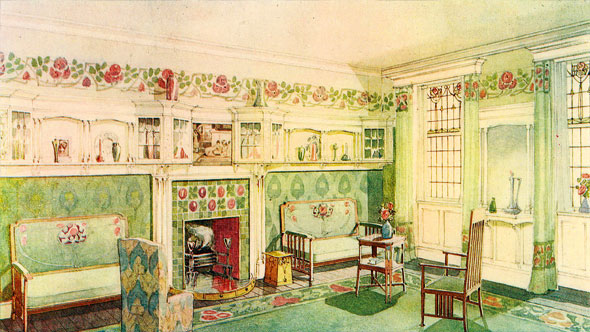

His more feminine furnishings and softer design styles were much in demand by interior designers, increasingly called upon to modernise oldfogey establishments. Until the end of the 19th century, ladies rarely dined in restaurants, but this was changing, and it became fashionable to be seen ‘at lunch’ in the grand London hotels such as Claridge’s and the Savoy. His design sensibility helped make the new female clientele feel at home, not least because many of them had also bought wallpapers and fabrics from his eclectic selection.

A watercolour sketch of a drawing room designed by Liberty in The Studio Yearbook, 1906

A watercolour sketch of a drawing room designed by Liberty in The Studio Yearbook, 1906Having discovered early on that Eastern fabrics were too delicate to be used by dressmakers and furnishers, Liberty sourced English dyers and presented them with Eastern-inspired designs to copy. His ‘Liberty Art Fabrics’ were hand-printed with wooden blocks. Peacock feathers and exotic flowers, overlaid on reeds and bamboo or complex shades of green, became enduring motifs. He wanted to give the ordinary person the chance to buy beautiful things.

Most famously, he worked with (and subsequently bought) Littler’s, a small printing company in Merton Abbey, southwest London. When Arts and Crafts designer William Morris acquired a paintworks downstream on the River Wandle, Liberty apparently joked, ‘We send our dirty water down to Morris.’

From left: A bathroom in Tjolöholm Castle, Sweden – a fine example of Liberty’s Arts and Crafts style. Wallpaper designed by Charles Voysey in the 1890s

From left: A bathroom in Tjolöholm Castle, Sweden – a fine example of Liberty’s Arts and Crafts style. Wallpaper designed by Charles Voysey in the 1890sFrom the 1890s onwards, he was cultivating symbiotic relationships with all the major and emerging designers in the Arts and Crafts and art nouveau movements. Such was the level of his patronage that the Italian term for art nouveau is Stile Liberty. However, according to Martin Wood’s beautifully illustrated new book Liberty Style, Liberty disapproved of the Continental curved excesses of the movement that we more commonly associate with the Paris Metro signage, preferring instead the more constrained, Celtic, visual language of Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Archibald Knox in particular.

Furniture was key to his success, as were the exquisite glass and pewter jugs and vases that resulted in clients vying for a place on the waiting list. But it was perhaps the ‘costume’ department, which he introduced in 1884 under the direction of the theatrical designer Edward Godwin, that contributed greatly to his legacy. It was here that the bolts of elegant Liberty silk would be transformed into gowns to rival those of the Parisian fashion houses. Godwin insisted at the time that dresses should not rely on ‘stiff, ready-made ornaments’, but on ‘the exquisite play of light and line’. It is a design principle that still holds true today.

Liberty Style, by Martin Wood, is published by Frances Lincoln, priced £35.