Drawing on the Imagination

Nevertheless, he started young, and the magazine Punch, which he illustrated while studying at Cambridge, was his springboard.

‘There was a column called In The City/In The Country. One side was about finance, the other about the countryside,’ he says. ‘You had to do two little drawings mashed up – I enjoyed that. More importantly, it paid me every week so when I stopped being a student it helped keep me alive.’

He went on to illustrate the magazine’s covers and it was a comment from the art director that helped shape his distinct style. He simply said that Blake’s rough sketches were far better than his finished drawings.

‘They were better in some respects. They were livelier. The editor noticed that the roughs were spontaneous and had more life in them. After that, I thought, “Oh, that’s all right, you’re allowed to be a bit free and easy.”

‘Of course, what took me years and years was to work out how to get the finished drawing exactly as I wanted it, but with the spontaneity that I had in the rough. To keep it alive.’

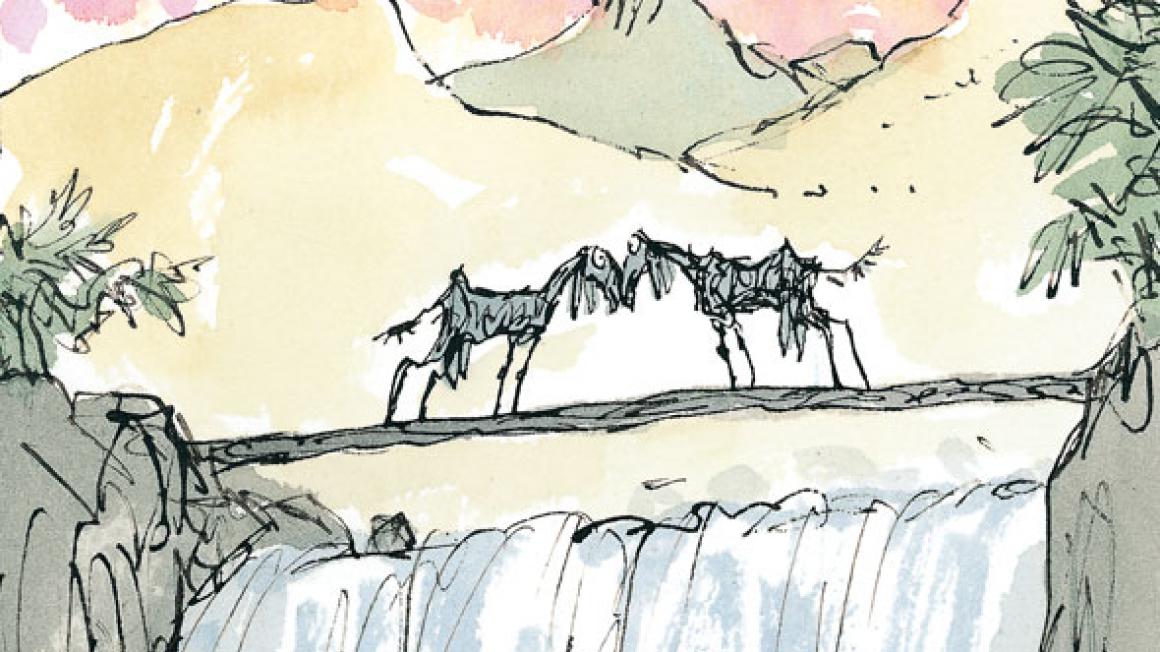

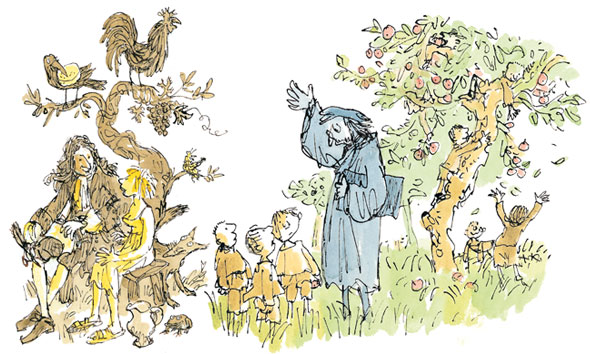

His latest project is Fifty Fables Of La Fontaine, a collection of the muchloved animal tales of 17th-century Frenchman, Jean de La Fontaine.

‘I enjoyed it so much that some of the drawings I kept doing again and again to see what it would look like. So there are a lot of extra drawings I didn’t use, which are OK as pictures but weren’t quite right for the book.’

So was it daunting working on stories that so many artists have already illustrated?

‘Sort of. But in a way, La Fontaine has been done so many times that it’s levelled out – you’re not competing with just one person. It’s open to a lot of interpretation.’

Blake particularly enjoyed illustrating the fable of Death And The Woodcutter. ‘There is a boy struggling along with a lot of logs and he decides it’s hopeless and calls on Death. Death appears and asks, “How can I help?” And the boy replies, “You couldn’t help me with these logs, could you?” It’s a punch line, not a fable really, but it’s a wonderful thing to draw.’

Many of the books Blake has illustrated have some sort of moral message at their heart. Is this merely a coincidence? ‘I’m not so concerned about there being a moral, but it’s nice if they are about something or about people and how they behave.

‘There are lots of children’s books about that, especially teenage books. They’re more concerned with life than adult books sometimes. There is one story I love about a dancing frog [Blake’s The Story Of The Dancing Frog]. A woman who’s married to a naval officer who is lost at sea finds a frog dancing on a lily pad and takes it home. It goes on the stage and it dances at the ballet, with Isadora Duncan and such.

‘There are jokes and it’s great to draw, but it also makes you think about what you do when you’re sad. You find something: in this case, it’s a dancing frog, but really it’s a metaphor for anything.’

With such a wealth of fabulous stories to illustrate, does he ever get illustrator’s block?

‘No, not really, it’s one of the things that our lot has over your lot,’ he laughs. ‘The advantage of being able to draw is that you can start a drawing without knowing what it is.

‘With writing, you need to have the beginnings of an idea of what you’re going to write. Inspiration, for me anyway, is not a bolt of lightning, you don’t suddenly go, “Ahh, I’m inspired!” It’s something that accumulates.

‘I don’t rely on inspiration, it doesn’t come into it. Sometimes you start drawing and nothing happens and sometimes it takes “life”. I’m no good at cookery but if you’re making mayonnaise you have to stir it and stir it and then suddenly it becomes mayonnaise – although sometimes it doesn’t.’

So how does he begin?

‘I often work on books, so you start to draw once you’ve read through the text. You get different amounts of information from the text – if it says he has a ginger beard and spectacles you start off with that.

‘Then you draw a few pictures of those people in different situations. It’s funny how it develops, because you do these rough drawings and by the time you’ve drawn that person a few times, you start to think you know what they look like, like you’ve met them. It’s very curious – you look at the earlier drawings and you think that doesn’t look like her. But of course that’s because she didn’t exist.

‘I talked a lot with Roald Dahl and the characters were particularly important. We modified The BFG because it was his idea that he should wear different things. I’m terribly well behaved; I just draw what it says.

‘But the real collaboration is with the words of the book. That’s what you’re feeling for, the atmosphere.’

He has also illustrated David Walliams’s children’s books, Mr Stink and The Boy In The Dress.

‘The first book I did with Walliams I hardly talked to David at all. I did one drawing of Dennis [from The Boy In The Dress] to begin with to go on the cover, although you really want to do that last because then you know everybody. So I had to imagine what Dennis was like and somehow I got it right. David said he sort of recognised him, which is very touching, actually. He said that he almost cried.’

Of course, Quentin Blake’s name will always be synonymous with Roald Dahl. But for an artist who has done so much more than work on Dahl’s books (his recent work includes some well-received nudes), I wonder if he resents his link to the world’s best-known children’s author.

‘If my way of drawing had only existed in Dahl’s books, then maybe, but I’ve never felt that. They were tremendously enjoyable to do.

‘I think if I had never done anything else I might have mixed feelings about it. By the time I started working with him I was 40-something, I knew how I drew; that is a nice thing because you can be the person you are no matter which writer you work for.’

For many of us, the books of Roald Dahl were a large part of our childhoods. How does it feel to be loved by children (and adults) around the world?

‘It’s lovely and slightly strange. It’s something you gradually find out later on. You know that Roald is very successful around the world, but then people tell me that they’ve had this book for 20 years and now they are reading it to their children.

‘That’s very affecting, I think. It’s very nice that that happens.’

Fifty Fables Of La Fontaine, selected and illustrated by Quentin Blake, is a limited-edition book published by The Folio Society, priced £245. To purchase a copy, call 020-7400 4200, or see

www.foliosociety.com/book/FLA/fifty-fables-la-fontaine