We know her as Picasso’s lover, his Weeping Woman,’ says Tate curator Emma Jones. ‘But this first full survey in the UK of Dora Maar’s work, spanning more than six decades, reveals her as a gifted artist in her own right.’ Jones is the co-curator of a Tate Modern exhibition that seeks to redress this injustice. Such a show is long overdue, as the achievements of female artists who were overshadowed at the time by their lovers or husbands – such as Lee Miller and Man Ray, and Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera – are being explored afresh.

The exhibition is endlessly surprising. It is striking how successful and original Maar was before she met Picasso in 1936 – she ran a successful fashion photography studio, her street photography was powerful, and her surrealist photomontages were haunting and witty. Her best work is unforgettable.

Born Henriette Theodora Markovitch, in Paris in 1907, she preferred to be called Dora. Her mother was French and owned a boutique, and her father was a Croatian architect. She attended Paris’s most progressive art schools and began working with photography in the late 1920s, encouraged by Henri Cartier-Bresson. ‘Within just a few years she built up a photographic practice of remarkable variety, spanning assignments in fashion, advertising and social documentation, creating wildly inventive images that came to occupy an important place in surrealism,’ says Jones. Her work was also published in arts journals and erotic reviews.

The exhibition opens with striking portraits made by Maar or taken by well-known photographers close to her, such as Brassaï, with whom she shared a darkroom, and Cecil Beaton, Lee Miller and Irving Penn. Beyond their friendships, these artists were all linked by overlapping professional activities and left-wing sympathies.

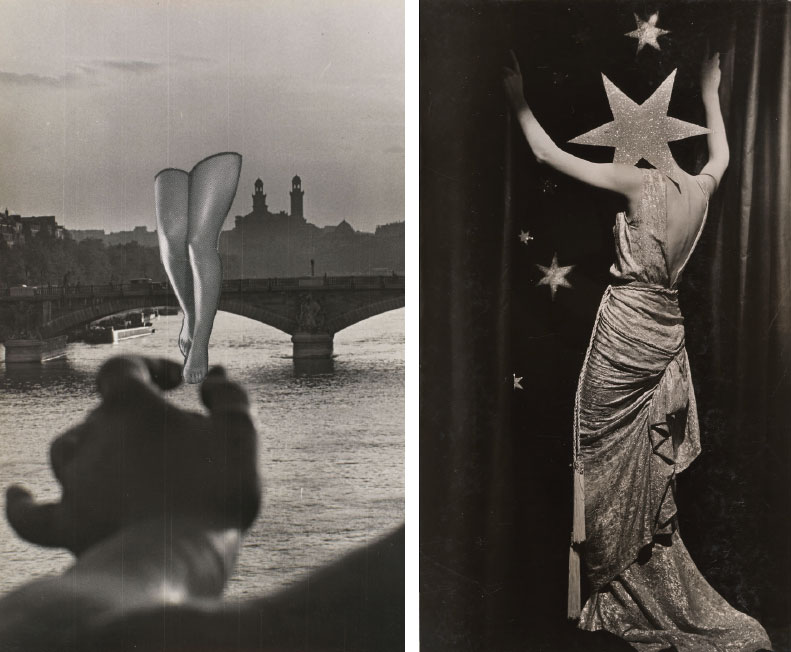

‘Much of Maar’s early work was darkly glamorous fashion photography, dramatically lit and ahead of its time,’ says Jones. She experimented restlessly with light and dark, using shadows to create atmosphere and the innovative technique of double-exposure. You can immediately recognise her work, which often has a peculiar, witty quality with a tinge of erotic strangeness.

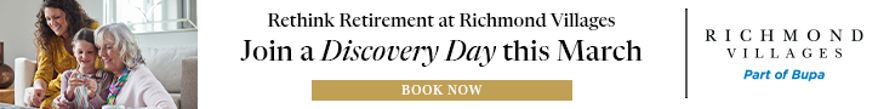

She was fond of using uncanny, surreal juxtapositions, such as a two-headed calf rising atop a classical fountain, and a beautiful woman’s face seen through a spider’s shimmering web. The best of her pictures are very dramatic. To expand her reach, Maar travelled to Barcelona and London during the Great Depression and took quiet, profoundly moving pictures of half-starved people in rags. She also documented the wretched inhabitants of ‘la zone’ – the shantytown on the fringes of Paris.

Maar was both a romantic surrealist and a gritty realist. I particularly admired her image of young saleswomen laughing behind a charcuterie stall in Barcelona. She creates a pyramidal composition using the angle formed by the arms of two of the women. It seems likely that Maar had been chatting in Spanish with them – having spent her childhood in Buenos Aires, she was fluent in Spanish as well as French.

In London’s East End she photographed a pearly king and pearly princess collecting money for Empire Day, and a woman selling lottery tickets beneath the steel pillars of the Midland Bank on Oxford Street.

Much of this powerful early work, however, was neglected after she fell in love with Picasso.

‘In the winter of 1935, Maar first crossed paths with Picasso, who was 26 years her senior and already a world-famous artist,’ says Jones. ‘When she was at the height of her career and being widely exhibited, he was emerging from a creative crisis, later described by him as “the worst time of my life”. He had not sculpted or painted for months.’

His love affair with the beautiful Marie-Thérèse Walter had burnt out and he was still married to Olga Khokhlova, a highly strung Russian former ballet dancer. Picasso first spotted Maar in Les Deux Magots café in Paris, as she repeatedly stabbed a knife between her black-gloved fingers, occasionally missing and drawing blood – a dark, surrealist performance. He watched mesmerised and asked Maar for the bloodstained gloves, which he preserved.

She soon became his lover and at first their relationship seemed reciprocal and nurturing. ‘As artists working in close quarters, the couple pushed one another into new creative territories. Maar taught Picasso about photography and printmaking, and he encouraged her painting,’ explains Jones.

With her dark, strong-featured face, Maar bore a marked resemblance to Picasso’s beloved mother. She even spoke Spanish so they could converse in his native language about their friends, art, and the tumultuous political events of the 1930s. Some credit Maar with politicising Picasso, and Jones thinks she was the most intellectual of his muses.

He painted her over and over again, most famously in the guise of Weeping Woman (1937), which visitors to the exhibition can see – Jones is keen to point out that the anguished picture is a symbol, rather than an actual portrayal of Maar.

‘As a photographer, Maar captured Picasso creating his best-known painting, Guernica (1937), in a series of photographs, and worked on her own paintings alongside him in the studio,’ says Jones. ‘Their creative relationship was much more collaborative than is usually portrayed.

For the next eight years they were central to one another’s lives, although Picasso refused to end his relationship with Walter, with whom he had a daughter, causing Maar much anguish.

A centrepiece of the exhibition, The Conversation (1937), Maar’s little-known painting dealing with her complex feelings for Picasso, is being shown in the UK for the first time. Created in the same year as Guernica, the canvas features Maar and Walter sitting back to back, like duellers, in a red interior, under an electric lamp. ‘Picasso borrowed the feature of the lamp above the two women for Guernica,’ says Jones.

Although Picasso had been originally attracted to Maar’s intense, personality, her independence soon triggered his rages and he sneaked back to the more pliable and adoring Walter. For years he undermined both women, playing them off against each other, relishing their jealous fights when they met in his studio.

It was in her poetic, surrealist photomontages that Maar achieved her best work. In my favourite, a graceful hand crawls from a conch shell against a stormy sky. ‘Maar made only 20 of these artworks before returning to painting,’ says Jones. ‘She would devote herself to it for the remainder of her life, though these works were rarely exhibited after the 1950s. It is only since her death in 1997 that the full breadth of her output has begun to be realised.’

A saucy surprise in the show, several of Maar’s beautiful, playful nudes of both sexes first appeared in various 1930s French erotic magazines such as Secrets du Paris, and Seduction.

Although Picasso had numerous love affairs, Maar was undoubtedly the most influential of his muses. Yet it is clear that Picasso had a harmful effect on her art by steering her away from photography, which he looked down on, and towards painting. After their relationship petered out in the early 1940s Maar suffered a breakdown and moved to a house in Provence which Picasso had bought for her. She spent the remainder of her life there, painting in seclusion.

Perhaps she had felt the need for a change of creative direction and Picasso was not completely to blame. The final rooms of the exhibition are mainly filled with paintings that are less interesting than her photography.

This beautifully curated, fascinating show reveals the terrifyingly destructive power of passionate love – which can destroy as well as inspire great art.

- Dora Maar is at Tate Modern, London SE1, until 15 March. The accompanying book, Dora Maar, edited by Amanda Maddox, Karolina Ziebinska-Lewandowska and Damarice Amao, is published by Tate Publishing, price £40